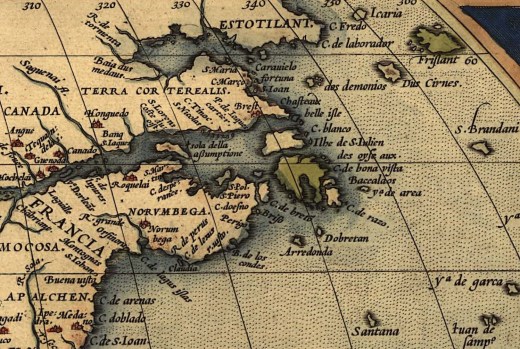

In 1675, the English occupation of Maine was limited to a narrow coastal band, extending from the Piscataway to Penobscot Rivers, and along the riverine valleys. The English clung to what early historian William Hubbard called the “sea border” and considered the unfamiliar woods behind them “a great Chaos, the lair of wild beasts and wilder men” (Maine History Online, 2010).

The most significant concentrations of English settlers were located at Cape Porpoise and Saco, Falmouth, the Pemaquid Peninsula, and along the Kennebec and Penobscot Rivers. The English population in Maine consisted of approximately 3,500 hardy souls in 1675, while the rest of New England, mostly Massachusetts, contained around 50,000.

As Siebert (1983, p.) describes Maine in 1675: “The largest and most important white community was Black Point, which included Prout’s Neck and Scarborough and extended from the Spurwink River west to the Nonesuch River. It counted more than 50 houses and had a population of about 650 people with a militia of 100 men. The Abenakis recognized Black Point as the strongest fortification in Maine and the most difficult to reduce since it had at least four strong garrison houses, those of William Sheldon, Joshua Scottow, Richard Foxwell, and Henry Jocelyn (Josselyn). Next in size was Casco Bay or Falmouth, which included the scattered habitations along the Fore River, on Munjoy Hill, and about the Back Cove and Presumpscot River, with a total of about 40 houses and 400 people. There were about ten other settlements from Kittery to Pemaquid.

As English society grew in the seventeenth century, hamlets evolved into towns, and forests and open lands increasingly gave way to the axe and the plow. This increased contact with the Wabanaki led to conflict. “The proliferation of fur traders and settlers profoundly disturbed the Abenaki way of life” (Baker, 1985, p. 13). As increasing numbers of fishermen moved into the Riverine valleys, they pushed the Wabanaki further back into the backcountry, away from their traditional coastal fishing grounds that they had relied on seasonally for food. This made them more dependent upon hunting game for food and obtaining English food supplies. The arrival of European fur traders also tied the Indians even more strongly to hunting. By 1675, the Wabanaki people had come to depend on English guns and ammunition for survival, abandoning their traditional methods of hunting. The stage was now well set for the coming wars.

The economy

The economy of Anglo-Maine was centered around agriculture, fishing, and lumbering. The prominent settler at Black Point, John Josselyn, remarked (Churchill, 2011, p. 66); “All these towns have stores of salt and fresh marsh [hay] with arable land. They are well-stocked with cattle. Josselyn also found Saco and Winter Harbor “well stored with cattle, arable land, and marshes.” William Hubbard indicated that “upon the banks [of the Sheepscot] were many scattered planters … a thousand head of neat cattle … besides … Fields and Barns full of Corn.” Further east lay Pemaquid, “well accommodated with Pastureland about the Haven [harbor] for feeding Cattle and some Fields also for tillage.” Fishing was also much in evidence. However, there were some regional differences in economic emphasis. Wells, Saco, Falmouth, and Sheepscot were focused on farming, while Cape Porpoise, Winter Harbor, Richmond Island, Damariscove, and Monhegan were concentrated on fishing.

The lumber trade also substantially impacted most of the European settled coast. As Churchill (2011, p. 67) describes, “… nearly every community had at least one sawmill, and a number had several…” The first mill was built by John Mason in 1634 on the Little Newchawnnock River (near Berwick). Although short-lived, it was followed by at least six other mills between 1648 and 1660. By the mid-1670s, York supported at least ten mills, while Wells and Saco each had three. Further east, the Clark and Lake swills in the Sagadahoc area readied a hundred thousand feet of boards for shipment in 1675. The Piscataqua area also provided numerous white pine masts and spars, many of which were being shipped directly to England” (Churchill, 2011, p. 67).

As the towns matured, they acquired many artisans, including blacksmiths, carpenters, millwrights, coopers, shoemakers, and tailors.

The French

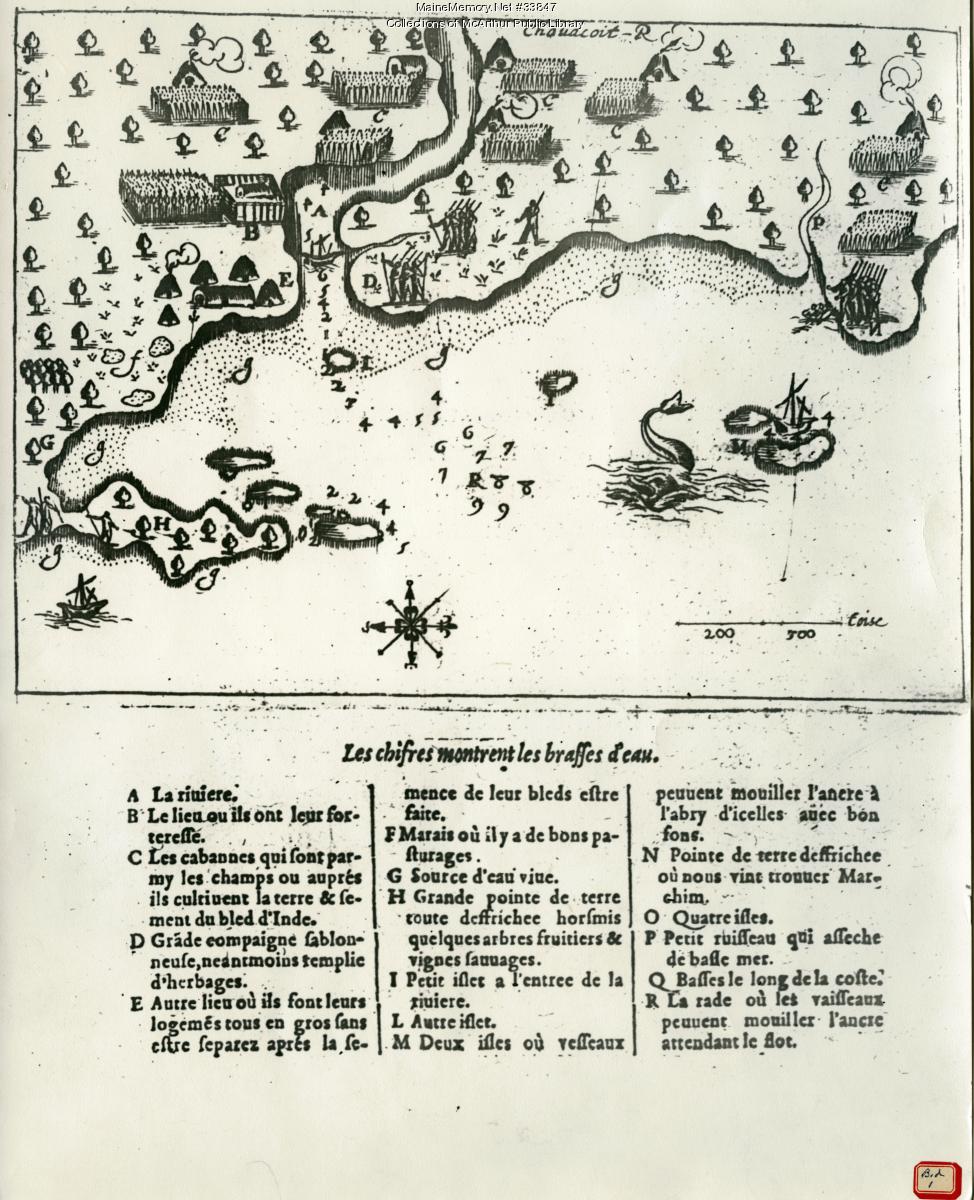

The French were in much smaller numbers than the English in Maine, located at trading outposts of varying duration at Pentagoet atthe mouth of the Penobscot River, St. Sauveur on Desert Island, Magies on the Machias River, and Port Royal in Nova Scotia. By far, the greatest concentration of Frenchmen was more south in the St. Lawrence Valley and Quebec, where about 10,000 lived.

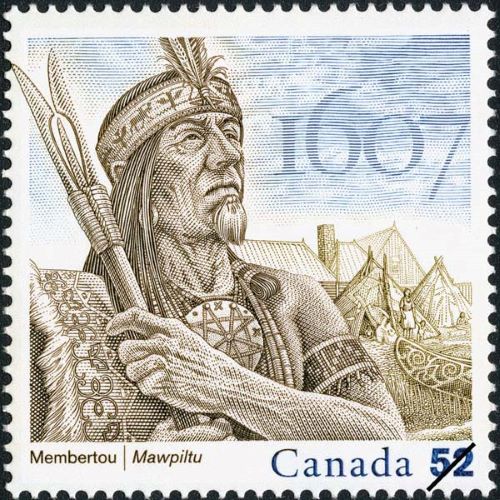

Overall, the Wabanaki felt much friendlier toward the French than the English, as they did not view the French as harboring the same expansionistic designs as the English. The French were almost entirely focused on the fur trade, and the Wabanaki would form strong alliances with them for that purpose. The French learned to speak fluent Algonquian and worked diligently to establish trading relationships based on mutual respect.

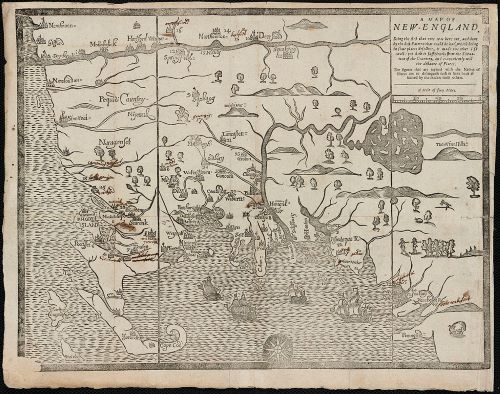

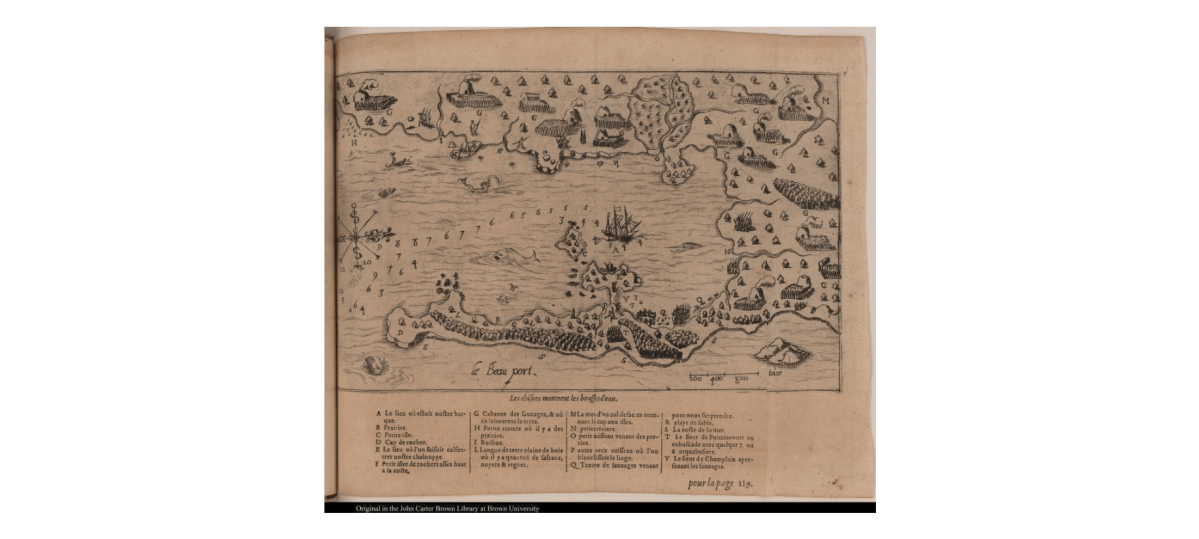

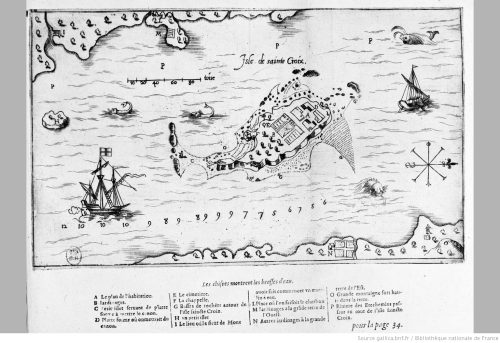

Illustration:

William Hubbard’s first map of New England (1667). From his “A Narrative of the Troubles with Indians in New England, from the Planting Thereof to the Present Time.” Originally published in Boston.

Bibliography:

Baker, E. W. (1986) Trouble to the eastward: the failure of Anglo-Indian relations in early Maine. Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. William & Mary. Paper 1539623765. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-mh0r-hx28

Churchill, E. (2011). English beachheads in seventeenth-century Maine. In: Judd, R.W., Churchill, E.A., and Eastman, J.W. (Eds.). Maine: The Pinetree State from Prehistory to the Present. University of Maine Press, Bangor. pp. 51–75.

Maine History Online (2010). 1668-1774, Settlement and Strife. Maine History Network. The Maine Historical Society, Portland. https://www.mainememory.net/sitebuilder/site/897/page/1308/print

Siebert, F. T. (1983). The First Maine Indian War: Incident at Machias. Algonquian Papers – Archive, 14. https://ojs.library.carleton.ca/index.php/ALGQP/article/view/837